By examining considerations from traditions that have examined intellectual virtues, we may come to better understand the virtues we need to develop our comprehensivity, our ability to comprehend our worlds broadly for context and deeply for clarity by taking seriously Buckminster Fuller’s aspiration of “wanting to understand all and put everything together”.

This resource will look at one 10 minute video lecture from Linda Zagzebski’s exquisite course on “Virtue Ethics”, produced by the University of Oklahoma, to spur our thinking about the intellectual virtues that might help guide our comprehensive practice, our comprehensive participation in our worlds. The result will give us an opportunity to review all 25 of our prior resources.

Intellectual Virtues

R. Buckminster Fuller’s approach to comprehensive thinking starts with Universe: “The universe is the aggregate of all of humanity’s consciously-apprehended and communicated experience”. This source for our learning can be seen as the collective cultural heritage of Humanity through all history. From this vast heritage, we have accumulated many traditions of inquiry and action. These traditions and their accumulated experiences are the sources for all our learning.

Comprehensive thinking is any effort to explore this vast inventory of experiences and traditions to address our concerns, intentions, and situations. In the resource The Measurements of Life, we learned that an interpretation is what to consider and how to consider it. So comprehensive thinking can also be seen as the process of forming interpretative stories building on our inventory of traditions and experiences. But to be comprehensive, comprehensive thinking aspires to further examine these stories with comprehensive measurement or assessments to form “adequately macro-comprehensive and micro-incisive” (Buckminster Fuller’s catchphrase for our comprehensivity) judgements to better engage our worlds and its peoples with understanding and effectiveness.

With this context for our exploration, what are intellectual virtues?

Our intellectual faculty refers to the regulation and guidance of our mental activities. So the intellectual virtues involve identifying exemplars, models, habits, or disciplines that can serve as guideposts to better organize our mental inquiries and actions.

To help us better tune into and identify intellectual virtues, let’s consider a short ten minute video lecture from 2015 by Linda Zagzebski:

Zagzebski reports that she wrote a book “Virtues of the Mind” in 1996 developing her thinking about how intellectual and moral virtues intersect with epistemology, the science of learning and knowing. Since I haven’t read her book, let’s focus on what’s in the video. Zagzebski says the motivation for intellectual virtues is “to get the truth about the world for ourselves and for others”. She adds, “we need to believe the truth for almost anything else we want”.

In the resource Shifting Perspectives and Representing The Truth, we learned from an exquisite 2016 video lecture by Tricia Wang that truth is always multi-perspectival. Wang went so far as to sternly caution us: “don’t trust the truth”. In that resource, I explained that truth can be seen as the coherence of a perspective or hypothesis with the experiences and beliefs that justify it. The recent resource on Judgment clarified that the justification for truth can now be seen as the process of organizing an adequate set of in-breadth and in-depth considerations, including ineffable or spiritual ones, to conscientiously evaluate the worth of our lives in our particular situation.

With these considerations of truth in mind, I would interpret Zagzebski’s use of the language of “the truth” as a shorthand to refer to effective judgment-making in support of effectively engaging our worlds and its peoples. That is, “the truth” can be seen as our guideposts for knowing that can assist us in making assessments. In that sense the truth is a motivation for identifying ways to help us better guide our mental activities with intellectual virtues.

Zagzebski highlights several intellectual virtues including curiosity, inquisitiveness, humility, open-mindedness, perseverance, attentiveness, thoroughness, and carefulness. Her guidepost for assessing all virtues is Aristotle’s great moral principle that the good lies at the mean between two extremes. That is, the assumption is that for each proposed intellectual virtue, we can have too much of it or too little and that virtuous behavior lies somewhere between these extremes. In the resource on The Whole Shebang, we introduced the adequate as an important way of considering the whole of a situation with our desiderata and intentions as a basis for judging breadth, depth, and value. The adequate has been our way of gesturing to something like the idea of Aristotle’s moral principle of the mean.

Aristotle’s mean suggests that the good is always some “intermediate between excess and defect” as my translation of the Nicomachean Ethics puts it. I prefer the notion of the adequate because it invites us to determine what may be necessary and sufficient for at least this particular inquiry or action while maintaining the advantages of Aristotle’s mean for avoiding harmful behavior such as analysis paralysis, value paralysis, and the paralysis of the whole (three dangers of comprehensive thinking discussed in the resources on The Necessities and Impossibilities of Comprehensivism, How to Create That-Which-Is-Not-Yet, and The Whole Shebang).

Broadly speaking, I like Zagzebski’s list of intellectual virtues. Curiosity, open-mindedness, and thoroughness entreat us to explore in breadth for context. Perseverance, attentiveness, and carefulness entreat us to explore in depth for clarity. Inquisitiveness is generally useful for both in-breadth and in-depth exploration. Her list broadly concurs with our approach to comprehensivity, our practice of striving to form broadly and deeply considered comprehensions about our worlds and its peoples.

I particularly like the way in which Zagzebski combines intellectual humility and open-mindedness in her observation that “intellectual humility makes us realize that we might be wrong about a lot of things. Open-mindedness makes us look at reasons for and against a belief.” This combination of two virtues comes pretty close to our virtue of mistake mystique, the realization that there will always be inherent gaps in our understandings, communications, actions, and outcomes which we should identify and strive to reduce (mistake mystique was developed in the resource on Mistake Mystique in Learning and in Life and elaborated on in the resource Redressing The Crises of Ignorance).

When Zagzebski says, “Part of being a person is having one’s own consciously developed point of view”, I think she means that our comprehensivity as everything we have learned in breadth for context and in depth for clarity prepares us to make adequate judgements to measure each particular situation. When Zagzebski adds that “Anybody who really treats all points of view as equal is not a person”, we first delight in the wonderful contradiction that the subject of her sentence, “anybody”, might not be a person! As we explained in the resource on Ambiguity, Contradiction, and Paradox, there is often a deep truth beneath many contradictions and paradoxes. I interpret Zagzebski to be pointing out that the very nature of our comprehensivity will incline us to some points of view. Admittedly, the experiences and traditions that we are most familiar with and most esteem will incline us to favor some points of view. She is right about that.

But, I feel the need to push back a little here: as explorers it behooves us to treat all points of view as equally valid so that we might seriously consider them all as we work toward developing an adequate weighing of the relative merits of each. Zagzebski is correct that life is short and we will not be able to thoroughly examine all possible views. The paralyses (mentioned above) that plague our ambition to be comprehensive must be contained. She is also correct that we will need to, putting it in my language, settle for a judgement of the adequate as we comprehensively measure any particular situation.

One advantage I find in the notion of the adequate is its ability to expand to require more breadth and clarity as we learn more. Learning is an iterative affair and what was adequate yesterday might not be adequate tomorrow because of all we learn today. We need intellectual virtues that aspire toward more and more breadth and depth as we learn more and more. I felt Zagzebski’s way of curtailing open-mindedness failed to impart this crucial value. She is correct that open-mindedness needs some bounds, but I would limit it with the notion of the adequate applied to particular situations, not the intermediate between abstract unchanging extremes.

What do you think of Zagzebski’s approach to intellectual virtues? Which intellectual virtues do you want to foster to improve the effectiveness of your participation in Universe.

What insights does her approach to virtues provide for our emerging tradition of comprehensive practice?

Epistemic Virtues for Comprehensive Practice

Linda Zagzebski’s exploration of intellectual virtues inspires us to wonder: What intellectual virtues might provide effective guideposts for our comprehensive thinking and doing?

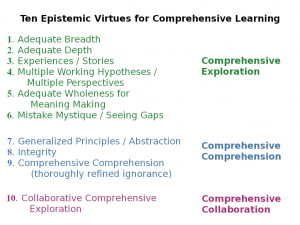

In the resource Comprehensive Exploration, Comprehension, and Collaboration, we summarized the first 18 resources in our resource center with a preliminary proposal for ten epistemic virtues for comprehensive learning. These epistemic virtues identify important values that can help us better learn in support of our comprehensivity, our ability to comprehend our worlds broadly and deeply. Now let’s shift to identify intellectual virtues for comprehensive practice.

Is there a difference between Zagzebski’s notion of intellectual virtues and the notion of epistemic virtues that I adapted from Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison in their 2007 book “Objectivity” (see the citation in the resource The Value of Multiple Working Hypotheses)? Although there may be nuanced differences between intellectual and epistemic virtues, I think the two terms are effectively synonymous. “Intellectual” evokes the ideas of the regulation of mental activities and “epistemic” evokes ideas about what qualifies as effective knowledge. But since the whole point of intellectual virtues is to qualify effective knowledge and since any sentient being seeking effective knowledge will need guidance for regulating their intellects, it seems clear that these are merely two aspects of the same thing. To avoid too much focus on the explorer’s own mind since we humans tend to quickly get self-reflective if not downright solipsistic when we look inward, I prefer epistemic virtues and its emphasis on guidance about what should qualify as good knowledge rather than a focus on mental activities.

Zagzebski’s video on intellectual virtues provides good context for updating our list of epistemic virtues for comprehensive practice. Most of these virtues were first summarized in the resources on Dante’s Comedìa and Our Comprehensivity and Comprehensive Exploration, Comprehension, and Collaboration.

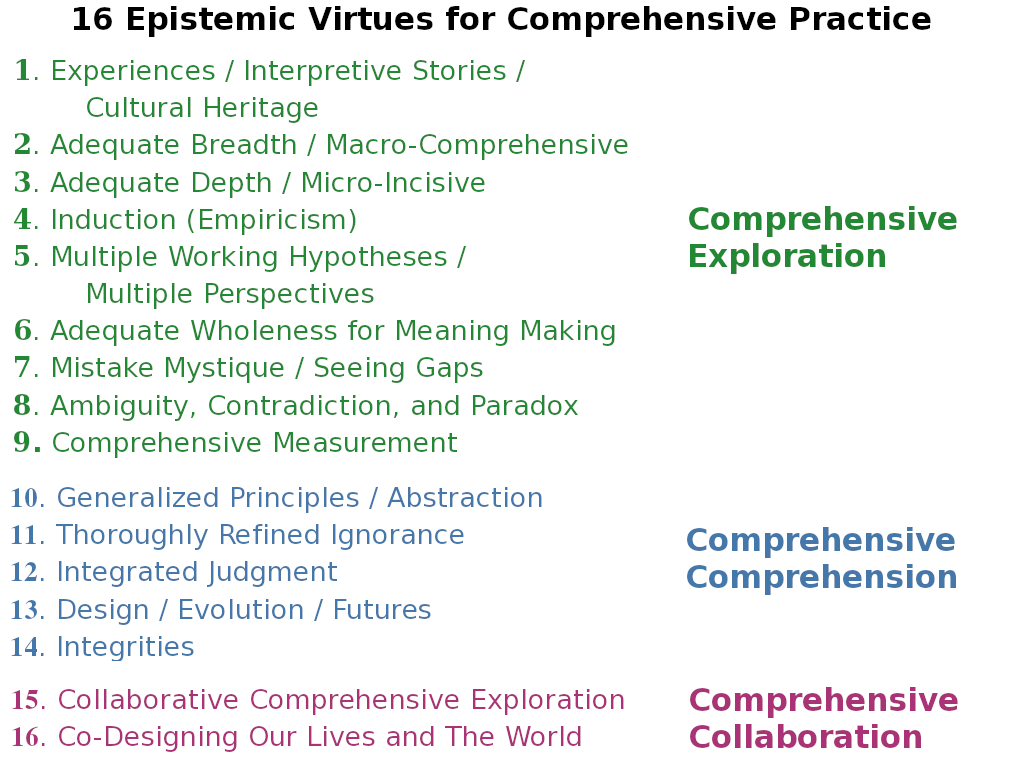

16 Epistemic Virtues for Comprehensive Practice

Nine Epistemic Virtues for Comprehensive Exploration

Coming to better understand the world and its peoples is a primary objective for comprehensive practice. Each of these nine epistemic virtues identifies tools to guide us when we are exploring.

𝟏. Experiences / Interpretive Stories / Cultural Heritage: The aspiration to source all our learning from traditions of inquiry and action that organize our experiences, interpretive stories, and cultural heritage. Each individual organizes all their learning into a Chronofile which always includes artifact enhanced memories even if dates and times are often omitted. Our inventory of experiences and our realization of its primary role in all our lives is the basic moral principle guiding comprehensive practice. It was introduced in the resource on Humanity’s Great Traditions of Inquiry and Action, developed in The Fundamental Role of Story in Our Lives, elaborated and reformulated in The Comprehensive Thinking of R. Buckminster Fuller, and further developed in the resources The Value of The Ethnosphere, The Ethics of Learning from Experience, and The Measurements of Life. The idea has been repeated, referenced, or reviewed in almost every other resource.

𝟐. Adequate Breadth / Macro-Comprehensive: The aspiration to engage and accommodate a sufficiently large and diverse collection of experiences, stories, and traditions to adequately contextualize our explorations. Breadth and depth were introduced in the resource Humanity’s Great Traditions of Inquiry and Action and elaborated on in the resource on The Comprehensive Thinking of R. Buckminster Fuller and Ambiguity, Contradiction, and Paradox.

𝟑. Adequate Depth / Micro-Incisive: The aspiration to comprehend each subject we explore in as much detail and with as much clarity or rigor as we judge reasonable given our situation. The limitations on the breadth and depth of our comprehensivity was first explored in the resource The Necessities and Impossibilities of Comprehensivism and reviewed in How to Create That-Which-Is-Not-Yet. The adequate was developed in the resource The Whole Shebang.

𝟒. Induction (Empiricism): The aspiration to infer hypotheses or proposals for true beliefs from considered experiences and to evaluate them by assessing their coherence with our full inventory of experiences perhaps supplemented with new voluntary experiences or experiments devised to test them. Induction was introduced in the resource The Inductive Attitude: A Moral Basis for Science and Comprehensivism, discussed further in Comprehensivism in the Islamic Golden Age, and expanded on in The Ethics of Learning from Experience.

𝟓. Multiple Working Hypotheses / Multiple Perspectives: The recognition that there are always multiple perspectives from which to consider a subject or situation and multiple hypotheses that may help us understand it. Therefore, comprehensive inquiry and action aspires to identify and consider an adequate set of perspectives and hypotheses to inform our analytical, synthetic, and integrative imaginations. Multiple working hypotheses were explored in the resource The Value of Multiple Working Hypotheses and multiple perspectives were explored in the resource Shifting Perspectives and Representing The Truth.

𝟔. Adequate Wholeness for Meaning Making: The recognition that the meaning making process involves the dynamics of gestalt shifts and gestalt crystallizations that bring into focus identified complexes of interdefined, resonant relations that form significant wholes. Jan Zwicky highlights this idea as “the experience of meaning” as discussed in the resource “to understand all and put everything together”.

𝟕. Mistake Mystique / Seeing Gaps: Realizing that there will always be inherent gaps in our understandings, communications, actions, and outcomes, mistake mystique is the aspiration to identify and further minimize these gaps through iterative comprehensive exploration and design. Formulating good and sometimes naïve questions can help us identify and negotiate these gaps. Mistake mystique was introduced in the resource Mistake Mystique in Learning and in Life and elaborated on in the resource Redressing The Crises of Ignorance.

𝟖. Ambiguity, Contradiction, and Paradox: The aspiration to lean into and deeply explore the ambiguity, contradictions, and paradoxes we encounter in our explorations in the hopes of gaining access to the creative wellspring of developing great ideas and truths. William Byers demonstrates the fundamental importance of these virtues in mathematics as introduced in the resource Ambiguity, Contradiction, and Paradox.

𝟗. Comprehensive Measurement: The aspiration to form a judgment assessing a subject or situation by integrating an adequate set of particular in-breadth and in-depth measures where each is evaluated in regard to its affects on the worth of our lives. Nondemonstrative including ineffable measures should be considered along with demonstrative ones. Comprehensive measurement was introduced in the resource The Standard for All Measurements: Our Judgment.

Five Epistemic Virtues for Comprehensive Comprehension

If we take seriously Buckminster Fuller’s aspiration “to understand all and put everything together”, after sufficient preliminary exploration we should aspire to integrate our knowledge into a whole picture comprehension of the way things are. Comprehensive comprehension is the general designation for these integrative and consolidating virtues or practices.

𝟏𝟎. Generalized Principles / Abstraction: The aspiration to find principles or relationships that abstract and accommodate vast subsets of our accumulated inventory of experiences. We learned in the resource “to understand all and put everything together” that these principles typically manifest as meaningful wholes that need to be carefully tested with our induction, our mistake mystique, and comprehensive measurement. The most powerful principles are often developed through careful explorations of the ambiguity, contradictions, and paradoxes in our subject or situation. Generalized principles were introduced in the resource The Comprehensive Thinking of R. Buckminster Fuller and further developed in the resource on Redressing The Crises of Ignorance.

𝟏𝟏. Thoroughly Refined Ignorance: The aspiration to structure all our learning with a fabric of questions which systematically interrogate the gaps identified by our mistake mystique. That is, to situate all our experiences, perspectives, hypotheses, ideas, and generalized principles in a fabric of thoroughly refined ignorance. The hope is that this network of questions and ideas will better inform our judgment. Refined ignorance was introduced as the “Hypostasis of Knowledge” based on Stuart Firestein’s idea that ignorance drives science and Buckminster Fuller’s mistake mystique in the resource on Redressing The Crises of Ignorance and expanded on in the resources on Comprehensivism in the Islamic Golden Age, Shifting Perspectives and Representing The Truth, “to understand all and put everything together”, Dante’s Comedìa and Our Comprehensivity, and What Is Comprehensive Learning?

𝟏𝟐. Integrated Judgment: The aspiration to better inform our judgment with comprehensive measurement instead of or in addition to a thoroughly refined ignorance, or perhaps, based on some yet-to-be-identified approach(es). I’ve separated judgment from thoroughly refined ignorance to make explicit judgment-making as a form of comprehensive comprehension. This virtue was introduced in the resource on What Is Comprehensive Learning? and developed further in The Standard for All Measurements: Our Judgment.

𝟏𝟑. Design / Evolution / Futures: The aspiration to navigate the big picture of it all through the conceptualities and practices of design, evolution, and futures. These ideas were introduced in the resources on Rethinking Change and Evolution: Is Genesis Ongoing?, How to Create That-Which-Is-Not-Yet, How To Explore The Future (and Why).

𝟏𝟒. Integrities: The aspiration to integrate all our comprehensive practice into a comprehensively integral whole, into an integrity. Bucky’s approach to omni-integrity was introduced in the resource Chronofiles: Data Mining Your Life for Comprehensive Thinking. For the time being, I’m thinking this is a catch-all category, hence “integrities” is plural. We need a place for the integrated wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita and the Tao Te Ching, which the 52 Living Ideas group has explored in depth. I see it as the task of those who have been studying these wisdom traditions to scope them and measure them against our ever-evolving set of epistemic virtues for comprehensive practice. I think such wisdom traditions and all the other universalist traditions of inquiry and action offer some way to think of the integrity of it all. How do we map them into our list of epistemic virtues for comprehensive practice? The universalist traditions were introduced in Humanity’s Great Traditions of Inquiry and Action and considered further in The Comprehensive Thinking of R. Buckminster Fuller and What Is Comprehensive Learning? We first attempted to summarize integrities in Dante’s Comedìa and Our Comprehensivity and developed it in Comprehensive Exploration, Comprehension, and Collaboration and in What Is Comprehensive Learning?.

Two Epistemic Virtues for Comprehensive Collaboration

We are a predominately social phenomenon; our language, most of our ideas, rituals, and technology have all been almost exclusively inherited from others. To be effective and relevant comprehensive practice must engage this social world by becoming a collaborative enterprise.

𝟏𝟓. Collaborative Comprehensive Exploration: The aspiration to listen to and work with others by sharing our individually articulated experiences, perspectives, hypotheses, ideas, and comprehensive comprehensions to collaboratively compose new understandings of our worlds and its peoples. This idea was introduced in the resource on Redressing The Crises of Ignorance as a reformulation of Buckminster Fuller’s ideas about education automation. It was summarized in Dante’s Comedìa and Our Comprehensivity and Comprehensive Exploration, Comprehension, and Collaboration. It was elaborated on in What Is Comprehensive Learning?

𝟏𝟔. Co-Designing Our Lives and The World: The aspiration to design our lives, our society, and our civilization through our conscientiously and collaboratively developed comprehensivity. Collaborating for Comprehensivity was conceived as a collaborative way of working together to re-design our worlds. This idea was introduced in the resource on The Comprehensive Design of Our Lives and further developed in What Is Comprehensive Learning?

While our schema of 16 epistemic virtues may be adequate for guiding and summarizing the tools of comprehensivity sketched out so far, I am sure it will be revised further as we continue to explore our vast cultural heritage and integrate more traditions of inquiry and action. I think Linda Zagzebski’s intellectual virtues are included in our system, but her list of virtues is so basic, so fundamental, that they form a cross-cutting substructure that our list builds upon.

What intellectual or epistemic virtues are most important for your comprehensivity?

What would you add to our list? What would you remove or revise?

What virtues guide you in designing your life, your society, and your civilization?

Virtues and our Comprehensivity

Every tradition of inquiry and action highlights qualities and behaviors which that tradition views as good. The late great philosopher Kenneth Taylor poignantly observes that we are “norm-mongering creatures” (see this short 1 minute video).

Norms and virtues may be the most basic human ideas as Taylor suggests. Our comprehensivity is the quality of our lives that works toward building our lives and our civilization by forming ever more extensive, ever more intensive, and ever more integrated understandings of our worlds and its peoples. To govern or regulate our comprehensivity, we have identified 16 virtues to help us explore, integrate, and participate in the world comprehensively. It is a good start, but our task is not close to being finished: we have barely scratched the surface of the available traditions to better inform our project.

What ideas from other traditions of inquiry and action from our vast cultural heritage do you think we need to incorporate into our list of epistemic virtues to better help us understand it all and each other?

It is a big project. We need your help to better explore all our cultural heritage to find the tools that will further our quest.

This essay was written to provide ideas in support of the 12 October 2022 session of “Comprehensivist Wednesdays” at 52 Living Ideas (crossposted at The Greater Philadelphia Thinking Society).

Addendum: 1h54m video from the 12 October 2022 event:

Read Other Resource Center Essays

- The Standard for All Measurements: Our Judgment

- Measuring Beliefs

- The Measurements of Life (Tools for Comprehensivity)

- What Is Comprehensive Learning?

- Articulating Comprehensivity: The Comprehensive Design of Our Lives

- Tools for Comprehensivity: Ambiguity, Contradiction, and Paradox

- Comprehensive Exploration, Comprehension, and Collaboration

- The Ethics of Learning from Experience

- Dante’s Comedìa and Our Comprehensivity

- Chronofiles: Data Mining Your Life for Comprehensive Thinking

- The Whole Shebang: “to understand all and put everything together”

- Shifting Perspectives and Representing The Truth